Today is Memorial Day. My thoughts are with my father, whose ashes are buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Dad—Big Red, dubbed so in his youth, because of his enormous red pompadour—is the greatest man I have ever known. My thoughts are with my mother, who is no doubt visiting his grave today, and exchanging private words, thoughts, and prayers with the love of her life. I am troubled that I cannot be there for both of them on this sad day.

But I did want to take some time to post a piece that I thought was appropriate to the true meaning of the last Monday in May—a day that has come to mean so many different things, to so many different Americans. Quite frankly, I believe this is a eulogy that we all need to read.

We need to take a step back, take a deep breath, and read this. We live in tumultuous times. The Pickford Word’s offering for Memorial Day is the Saga of The Four Chaplains. As much as any other war story, we feel it represents precisely the somber, noble, patriotic, and self-sacrificing nature of the day.

The story is a chapter excerpt from one of our books, “Wigger”, and we have chosen to also excerpt here the chapter which precedes the Saga of the Four Chaplains. Why? Because, in addition to being a story about love of country, and love of one’s fellow man, the Saga of the Four Chaplains is a story about religious tolerance. And that is something that seems to be in very short supply these days.

And so we have preceded the Chaplains’ tale with a story of extreme religious intolerance, on the slim hope that we might shame the narrow minded among us into opening up their hearts, and remind the rest of us to be ever vigilant, about our own lurking prejudices. We may not always be at war. But that does not mean that hatred … that most elusive of enemies … is not always on the offensive.

“Of Heathens and Holier-Than-Thou's”

And while we're on the subject: lest anybody accuse me of being prejudiced, say, for example, against Baptists, America's South, Appomattoxins, or Lynchburgers, let me switch gears. This chapter comes to us from the lovely state of Connecticut, and has nothing to do with the Civil War, slavery, or Baptists.

An appalling thing happened after the shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary School.

I am not talking about the Sandy Hook tragedy itself, mind you, for most writers of any integrity have agreed that there are no words which can finally, completely, describe or encapsulate the horror and sadness of that day.

I am talking about an event you may have heard about; it happened shortly after the joint memorial service which was held for the victims, their heart-broken families, a grieving community, and a stunned nation.

I refer to the apology made to his flock by a Lutheran Minister, the Reverend Robert Morris, for his “gross misjudgment” in choosing to stand on the same stage with persons of other faiths. It was an apology demanded by his parishioners at Christ the King Lutheran Church. It was an apology for participating in a memorial service which included, according to the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod, “false religions.”

From the internet writ large, February 7th, 2013:

“LCMS president Matthew Harrison wrote in a letter to the Synod that ‘the presence of prayers and religious readings’ made the Newtown vigil joint worship, and therefore off-limits to Missouri Synod ministers. Harrison said Morris's participation also offended members of the denomination.”

For God’s sake, people. Twenty-six human beings were slaughtered, twenty of them mere children, quite nearly babies, and the best that the Reverend’s Congregation can come up with is that in merely standing on a stage with a Rabbi and a Muslim and a Methodist and an Episcopalian and a Catholic and a Protestant and a member of the Baha’i faith is somehow endorsing false religions? Somehow worshipping false gods?

For God’s sake people, it would be the beginning of a vaudeville joke if it weren’t so damnably tragic: “A Rabbi, a Priest, and a Lutheran walk into a bar. . .”

I do not blame the Reverend. By all accounts, he not only did a great deal of praying and soul searching prior to participating in the memorial service, but he spent a great deal of time explaining his reasoning to his congregation. In spite of his exhaustive efforts to make his flock understand, their best plan for dealing with the Sandy Hook Elementary School Shooting Memorial Service was to insist that their Reverend apologize for attending, and for participating.

Shame on them, I say.

What was their plan, I wonder? That each family of a dead child be swallowed up by their own personal church or temple congregation, with a memorial service to be carried out away from the community, away from those few other people who had shared such unthinkable loss—and who also were the only people who could completely comprehend and empathize (as opposed to sympathize) with what the bereaved were experiencing in that horrific moment?

But that is precisely the problem with the intolerant Synod’s plan.

There was only one place that the parents of those twenty children, and the families of those six brave adults, should have been, and that is with each other.

Any mental health care professional will tell you that in an overwhelming number of cases, it is only the ongoing communion with others who have gone through the same trials and tragedies that can lead to the only true healing which actually takes root and endures: war veterans know it, rape victims know it, drunks know it, addicts know it, cancer survivors know it, victims of terrorist attacks increasingly know it, and Parents of Murdered Children know it.

Hey, I get it. The whole religious intolerance thing. It has been my pleasure (after working on this very painful book during the day), to watch “The Tudors” in the evening, which is a very ornate and lush program about King Henry the Eighth, a little lax with the historical facts, thirty-eight episodes long, but the upshot goes something like this: some people believe that when you take Holy Communion, when you take the bread in your mouth and drink the wine (or, in more modern congregations, take the wafer and the grape juice), a miracle occurs and it actually becomes the body and blood of Christ. This restores the faith and inspires the soul, by the grace of the miracle of the transformation. Now, other people believe that when you take Holy Communion, when you take the bread in your mouth and drink the wine (or, in more modern congregations, take the wafer and the grape juice), it is a symbolic transformation, and this beautiful ritual serves to restore the faith and inspire the soul, by the grace of the symbol of transformation.

I, for one, can be friends with people from both groups, and will not share here in which group I place myself.

But in “The Tudors”, if you are in the wrong group (during the reign of the wrong wife), essentially, you will be hung from a high tree, with your wife and children hanging at your side. This may or may not be in addition to being drawn and quartered and, in the process, having your intestines stir-fried in a kind of Elizabethan wok while you are still alive to witness this ghastly appetizer being prepared.

The above paragraph contains very little exaggeration.

Millions of people—men, women, and children—have been slaughtered in grand and expansive religious wars and crusades, over just this kind of compounded minutia. These wars historically have been long and bloody and sadistic … and the thing is; I am fairly certain that this is not what Christ had in mind when he stood on a small butte and said all those pleasant things he said in the New Testament.

Yet this, I think, is the kind of pettiness we were seeing when this forced apologia actually became a side story of the Sandy Hook tragedy. This, when the side stories should have been devoted entirely and exclusively towards healing: stories about gun control, stories about increased school security, stories about whether or not the first responders are getting enough counseling, and from whence comes the funding for that counseling … stories about what is being done for the families who lost so ineffably much. . .

Sandy Hook, Connecticut is a tiny town. About 11,000 people. When I close my eyes and think of the Sandy Hook shootings, and all the attendant horrific images, I cannot shake from my brain the image of these self-righteous parishioners who, in all their unchristian pettiness, just could not think of anything to do with themselves in the hours and days that followed, other than to rag on their Reverend.

Can you not picture it: little groups, hushed phone calls, clusters of people chin-wagging. (“He shook hands with someone who prays to Mohammed! Doesn’t he know our country is at war?”) And who even knows what Baha’i is or means? At least a Lutheran understands enough about Methodists and Episcopalians to explain why they’re wrong. But Muslims? Why, there might as well have been Zoroasters and Druids praying on that stage.

In a world so full of religious intolerance and ultra-violence, I believe that the congregation of the church should be ashamed for focusing on divisive issues at a time when healing was so desperately needed. Are they really so very sure of every bit of minutia that they believe, yet at the same time so unsure about the strength of their chosen religion, that their faith is both sullied and threatened by sharing a memorial service with those of other faiths?

People, there was much that needed doing, and it was time to step up to the plate.

I KNOW TWO THINGS TO BE TRUE

First, it is always impossible to know exactly how one would act in such a situation—if I was a citizen of Sandy Hook, for example. But I do believe that if I lived in that town, and saw my fellow citizens in such indescribable grief and agony, I suspect that the first thing I would do would be to spend every waking moment on the phone to the airlines, all of the airlines—first reasoning with them, then begging them, then shaming them into creating seats on airplanes, so that the loved ones of the families could fly from wherever they were to Sandy Hook, Connecticut at this unspeakably tragic time. I know it’s Christmas, flights are busy and fares are high, but this would have been absolutely the right thing for the airlines to do. Somewhere, in the thousands of flights a week that soar through the skies of this country, there is room for a grandparent, an aunt or uncle, a college kid who has just lost their brother or sister.

There is nothing that can be done to lessen the pain of these grieving parents, but at least they don’t have to grieve alone. They should have been surrounded by as much family as could be rushed to their side, and effecting THAT EVENT is what I would have been doing, instead of feeling like my personal sect of the MISSOURI SYNOD LUTHERAN MOVEMENT was threatened by hearing someone in a community center use the word “Shiva”.

Surely we all know that monuments will be built to honor the dead and things like scholarships and charitable organizations will spring up to keep their memory alive; these require fundraising. Couldn’t those parishioners of various churches who have not suffered a direct personal loss get that going in their gossip groups?

And what can be done for those brave first responders? Let us set aside for a moment the fact that they risked their lives by walking into a building where there was a person (or persons) with a high capacity automatic weapon—let us imagine for a moment what they saw when they entered the school. These people saw six dead adult human beings and twenty dead children. Correction: two of the first responders carried barely breathing children in their arms out into a terrified crowd; those children later died. By their own admission, the first responders never expect to get over this.

From the Associated Press, December 20th, 2012:

Firefighter Marc Gold, who rushed to offer help even though his company was not called, said he is haunted by the trauma of the parents and the faces of the police who emerged from the building. “I saw the faces of the most hardened paramilitary, SWAT team guys come out, breaking down, saying they've just never seen anything like this,” said Gold, a member of the Hawleyville Volunteer Fire Department. “What's really scary to me is I'm really struggling, and I didn't even see the carnage.”

We have seen how our government has let down the first responders from 9/11. If I was a member of a Sandy Hook congregation, I sure as hell would make sure that didn’t happen on my watch.

And then, me and my fellow-flock, once we realized that the next holiday on the calendar after this tragic Christmas was Valentine’s Day, and after we had finished bemoaning the fact that those poor children would never have the opportunity to indulge in the time honored tradition of giving and receiving little pink and red missives exchanged between friends and baby crushes, I would remind myself and everybody else at the chinwag that Valentine’s Day has disintegrated from what it originally was—a story of acts of kindness exchanged between strangers—to a commercial holiday all about chocolate and flowers and lingerie and jewelry, a perversion which leaves most men stumbling about like beefheads, searching desperately for the perfect Valentine’s Day gift, yet knowing they’ll inevitably get it wrong, while most women are left feeling alone, homely, ignored, outcast, or inadequately gifted.

I would further urge the others in this chinwag that perhaps it is finally time to reclaim Valentine’s Day, and use it as a special time to remember and honor these children in perpetua with annual Februarial Random Acts of Kindness.

And if somebody didn’t know what I was talking about—since natural curiosity and love of history is dying a swift death in our culture—I would remind them that the original Valentine was a 3rd century priest, practicing Christianity at a time when the Romans were brutally persecuting them. In fact, the ruthless Claudius II was so hard-hearted that he did not allow the soldiers in his army to marry, fearing that husbands with wives and children would not fight so ruthlessly, so cruelly, and to the death, dreaming as they were of a happy return to hearth and home.

So Valentine came along and married these young lovers in secret, as a part of many Christian communions and rituals which he carried out behind the Emperor’s back. But when he was found out by the Emperor, he was thrown in prison to await execution. It was a sweet young blind girl named Julia, daughter of the jailer Asterius, who was to make Valentine’s last days bearable. She brought small gifts of kindness and comfort to Valentine’s cell, and in return, he prayed all night before he was to be executed, and her sight was miraculously restored. Hence, the “Saint” Valentine.

Miracles can and do abound.

And then I would say that this commercialized holiday has not only turned shallow, but leaves many feeling marginalized and excluded. But think about it ... who could be excluded, who could feel excluded by this holiday taken back to its humble yet miraculous beginnings, a holiday now dedicated to the bestowing of Random Acts of Kindness—to the elderly, to the isolated, to children in need, to souls in pain, to animals who are suffering … to anybody in need of the reassurance that we are not, none of us, in this alone, not if we reach out. And not if others are willing to reach out in return.

And it would be my hope that at this point, I would have to shut up because everybody else is talking over me and louder than me, brainstorming and brimming with ideas for Random Acts of Kindness, because Saint Valentine’s Day is less than two short months away … because the Sandy Hook shootings took place just before Christmas and Chanukah, on December 14th, precisely two months before Valentine’s Day.

And every act (doesn’t this go without saying), every gesture, (this much should be obvious), every Random Act of Kindness on this new Saint Valentine’s Day is dedicated to the 20 small souls who died at Sandy Hook, and to the 6 heroic grown-ups who gave their lives to save children.

These, my friends, are the kinds of discussions that I would have hoped my church would be having, in the heart-wrenching days and weeks that followed the tragedy.

Not wrenching an apology out of my minister for standing arm in arm with others who believe in a Higher Power, during this desperate hour of prayer.

I KNOW THIS SECOND THING TO BE TRUE

In the world we live in today, atheists and agnostics are springing up like mushrooms in a field of cow patties after a spring rain, and guess what—the new “converts” consist mostly of young people. Do the research through PEW and Gallop, or NSRI and ARIS, if you don’t believe me. Depending on whom you consult (different organizations have different agendas, obviously), between 25% and 56% of young people simply don’t believe in anything. And even if that low end statistic is true, one out of four, I personally find that both alarming and sad.

Why this growing trend?

Speak to these young people. I have. Also, I have read the research of others who have explored this topic, and they will all tell you why so many kids are now embracing atheism. Not because the world is going to hell in a handbasket. Crap, the world has always been going to hell in a handbasket, starting back in the Roman days when we threw live human beings to wild animals in the Colosseum for our personal amusement, through the outbreak of the plague, through the exploding of several Wars to end all Wars, to the dropping of atomic bombs, to the death of disco (no wait—that is proof of God) —to the imminence of our extinction by global warming and the greenhouse effect.

The world going to hell in a handbasket, in and of itself, has never been a reason to turn away from God. If anything, desperate times tend to make us more likely to seek God out— “There are no atheists in foxholes”, “Praise God and Pass the Ammunition”, and all that. (The latter phrase being an actual remark from a Pearl Harbor Chaplain made during the infamous attack, in addition to being a thigh-slapper of a song by Frank Loesser.)

No, it’s not gloom and doom that is nurturing along this new crop of atheists. Kids are turning away from religion because they are increasingly seeing it as dogmatic, intractable, judgmental, and divisive: no women may minister, gays are condemned to hell, non-Christians worship false gods (ergo are also condemned to hell), such-and-such a behavior alienates you from God, even thinking such-and-such is a sin. Etcetera.

Writes one secondary student in Maryland, known only as Skyler, “I’ve been called an idiot for not believing in God, which is quite rude, since it’s my opinion. I’ve gotten death threats. One person said he wasn’t scared of me, since he’s a ‘crusader.’ ”

And the Public Religion Research Institute has recently published findings that a whopping 43% of all Americans—many of whom do believe in God—find the messages coming out of religious establishments to be negative in their impact.

I have just three little words for you: Westboro Baptist Church.

The things that we all instinctively seek from religion—hope, inspiration, faith, strength through the tough times, a yearning for some better reality beyond this life—struggling to find a basic code of humanity in most any thriving religion today is getting more and more difficult; common sense notions about decency and kindness are being lost in a religious lexicon so complex that it makes an IRS publication look like the instructions for Shoots ‘n Ladders.

I keep my faith simple, and sincere. In the poem which terminates this book, I have written a closing line, which I suspect will be taken as inflammatory by many, but which really I see as just taking a load off my shoulders:

“My God will judge your god,” I say to Appomattox.

This is not a matter of the T-shirt I so long to purchase and wear on my ornery days: “My God can beat up your god.”

The joke is, see, is that it is God’s job to judge, not mine.

So put up the Big Top, invite everybody to the circus. I just want us to all play nice.

For my part, I am tortured by wondering if Adam Lanza, and all the shooters like him, might have not have committed this heinous act at Sandy Hook Elementary if he had not been bullied as a child—clearly an un-Christian act, which, even though it is sometimes learned from other kids, must at some point be learned from someone’s parents. What kind of spirituality are these parents practicing? Are they abusing their children? Maligning other races and faiths? And are they doing all of this at the same time that they religiously attend church on Sundays and declare their undying devotion to God?

I know that to be the modus operandi in Appomattox—for far too many sorry souls, at least.

At the Sandy Hook Interfaith Memorial Service, Anthony Cerritelli, a young Catholic man, was probably not pre-occupied that there were Lutherans in the audience and a Lutheran Reverend on the stage; he was surely lost in mourning the death of a woman he planned to propose to just a week later. He had even asked her parents’ permission just days before the shooting. Instead of slipping the ring on her finger on Christmas Eve, he slipped it on her finger a week earlier than planned, as she lay in her coffin. Rachel D’Avino is part of a very small and precious group of the dead: those who are buried with an engagement ring before the beloved had a chance to get down on one knee. And the fact that there was a Muslim and a Jew praying along with Rachel’s own parish priest on that stage probably was the farthest thing from Anthony’s mind.

And I can assure you that Veronique Pozner was not thinking about whether the Baha’i guy on the stage was a threat to her Judaism, or the Latin words of the Requiem were an affront to her Hebrew prayers.

She was thinking about her child’s lovely brown hair, his angelic long black eyelashes, and the sheet that covered the bottom half of his face because his jaw had been blown off. She was not thinking about religious differences. She was thinking about how her six year old son Noah, the youngest victim, had been shot eleven times. She was thinking about how she wanted to place the traditional white stones with an angel inside, into each of Noah’s hands, as he went to sleep forever. But she couldn’t put one in his left hand. Because didn’t have a hand any more, just a stump.

This woman needed all of the other parents of these poor innocent young victims around her. She needed all the comfort she could get. And all the prayers we could offer. All of the parents needed this. They needed to be at that particular memorial service, to be reminded that at the very least, they were not alone. If there was any service to which God and his angels would listen, it was this one.

So, if your religion is about preaching but never hearing, homilies where there should be humility . . .if it is about arrogance without tolerance, judgment without mercy—then I suggest you stop and rethink some things. In a sentence, get your petty head out of your self-righteous arse, and think about what other people are feeling for a while, before you start dictating what you are so sure your god thinks about all of this.

And if it is OK with your God, tonight, hit your knees and pray for these poor victims.

Charlotte. Daniel. Olivia. Josephine. Ana. Dylan. Madeleine. Catherine. Chase. Jesse. James. Grace. Emilie. Jack. Noah. Caroline. Jessica. Benjamin. Avielle. Alison. Rachel. Victoria. Mary. Anne. Lauren. And Dawn . . .

ADDENDUM:

That’s the problem with taking so long to fact check and proofread. It has been a busy news week. This was the week of the Boston Marathon. So add to your prayers … Krystal, Sean, Lü, and little Martin.

THE SAGA OF THE FOUR CHAPLAINS

"The finest thing this side of heaven ..."

As told by various eyewitnesses:

Coming on the heels of my screed about the Lutheran Synod at Sandy Hook, this following famous and inspiring story, moving in direct juxtaposition to the previous chapter, should need little introduction. Indeed, more prelude would be shabby.

“And remember, the Truth that once was spoken,

To Love another person is to see the face of God.”

—The Epilogue from “Les Miserables”

As sung by Jean Valjean and family

Arguably the most beautiful song ever written

*******

It was the evening of February 2, 1943, and the U.S.A.T. Dorchester was crowded to capacity, carrying 902 service men, merchant seamen and civilian workers. Once a luxury coastal liner, the 5,649-ton vessel had been converted into an Army transport ship. The Dorchester, one of three ships in the SG-19 convoy, was moving steadily across the icy waters from Newfoundland toward an American base in Greenland. SG-19 was escorted by Coast Guard Cutters Tampa, Escanaba and Comanche.

Hans J. Danielsen, the ship's captain, was concerned and cautious. Earlier the Tampa had detected a submarine with its sonar. Danielsen knew he was in dangerous waters even before he got the alarming information. German U-boats were constantly prowling these vital sea lanes, and several ships had already been blasted and sunk. The Dorchester was now only 150 miles from its destination, but the captain ordered the men to sleep in their clothing and keep life jackets on. Many soldiers sleeping deep in the ship's hold disregarded the order because of the engine's heat. Others ignored it because the life jackets were uncomfortable.

On February 3, at 12:55 a.m., a periscope broke the chilly Atlantic waters. Through the cross hairs, an officer aboard the German sub U-223 spotted the Dorchester, gave orders to fire the torpedoes, and a fan of three were fired. The one that hit was decisive—and deadly—striking the starboard side, amid ship, far below the water line.

Danielsen, alerted that the Dorchester was taking water rapidly and sinking, gave the order to abandon ship. In less than 20 minutes, the Dorchester would slip beneath the Atlantic's icy waters.

Tragically, the hit had knocked out power and radio contact with the three escort ships. The CGC Comanche, however, saw the flash of the explosion. It responded and then rescued 97 survivors. The CGC Escanaba circled the Dorchester, rescuing an additional 132 survivors. The third cutter, CGC Tampa, continued on, escorting the remaining two ships.

Aboard the Dorchester, panic and chaos had set in. The blast had killed scores of men, and many more were seriously wounded. Others, stunned by the explosion, were groping in the darkness. Those sleeping without clothing rushed topside where they were confronted first by a blast of icy Arctic air, and then by the knowledge that death awaited. Men jumped from the ship into lifeboats, over-crowding them to the point of capsizing, according to eyewitnesses. Other rafts, tossed into the Atlantic, drifted away before soldiers could get in them.

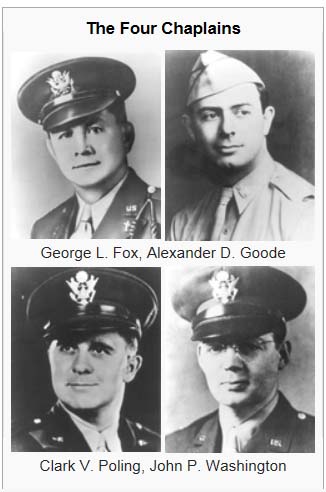

Through the pandemonium, though, four Army chaplains brought hope where there was despair, and light where there was darkness. Those chaplains were Lieutenant George L. Fox, Methodist; Lieutenant Alexander D. Goode, Jewish; Lieutenant John P. Washington, Roman Catholic; and Lieutenant Clark V. Poling, Dutch Reformed.

Poling was certainly one of the most humble and humanizing of the four, for he had the courage to write openly to his father and others of his fear that he might not have the courage to be strong when the test came. History would prove that he was to show courage almost beyond belief.

The Catholic Chaplain, Father Washington, was as much a buddy to the young soldiers (most of whom had never been away from home before), as he was a confessor, and it was not unusual to see him hanging out with the men—exercising, playing music, chewing the fat. Once, when asked to bless a hand of cards during a poker game, he simply eyeballed the close-to-the-vest hand and said, in his Irish brogue, "As though I'd waste my prayers on a lousy pair o' trees!" But it had been a long journey for Washington: this kind, strong man of God had been raised in Hell's Kitchen, and had been a member of a street gang growing up. But as a boy, he had become ill—so ill that a priest was brought in to give him last rites. The boy survived, and he believed it was because of the power of prayer. It was this miraculous turn of events that also turned the corner of his life, and made him want to be a priest as well.

Alexander Goode had wanted to be a Rabbi since his youth, and had made it part of his life’s work to fight religious intolerance. In 1941, Goode founded Boy Scout Troop 37 in York as a multi-cultural mixed race troop, the first troop in the U.S. to have scouts earn Catholic, Jewish, and Protestant awards. Although he was originally turned down when he applied to become a Navy Chaplain, his faith was stronger than his bruised ego; he applied again after Pearl Harbor and was accepted. He was very patriotic and eager to serve—for he had seen as early as 1931 what was happening in Germany, to the Jewish people, in particular. His writings, his teaching, and his preaching all helped to change everything from the educational structure of his hometown to the tolerance of a new world.

Fox, who had lied about his age and joined the Navy at 17, was a highly decorated veteran who had served in both World Wars. Even before stepping aboard the Dorchester, he had proved his heroism countless times. Once, while still just a boy driving an ambulance in World War I, he saw two soldiers who had been victims of a massive gas attack, both without masks. He stopped his ambulance, ran across the field, and put his mask on one of the soldiers, leaving himself to survive the gas as best he could. Twice he did this. By the time the Second World War had rolled around, Fox had been awarded the Silver Star, the Purple Heart, and the French Crois de Guerre. And even as he stood on the Dorchester, he knew that somewhere, fighting in some other theatre of war, was his son, who had enlisted in World War II the same day he had.

And then, during the voyage, one of the first "miracles" happened—at least by the standards of the day, and of the way that so many religions seem to be operating during those narrow times: each of the chaplains invited all of the men to their services, be they Friday night, Sunday morning, whenever. Perhaps it was boredom, or fear, or curiosity, or just a genuine desire to grow closer to God as the war itself grew nearer, but all the services, whether shepherded by a priest, a rabbi, or a reverend, were multi-denominational. It was really rather astonishing. Men were learning new traditions—and new tolerance. It was something one rarely saw on dry land. Not then, and not now.

But the fateful night of the sinking of the Dorchester would be their ultimate test.

Quickly and quietly, the four chaplains spread out among the soldiers. There they tried to calm the frightened, tend the wounded and guide the disoriented toward safety. "Witnesses of that terrible night remember hearing the four men offer prayers for the dying and encouragement for those who would live," says Wyatt R. Fox, son of Reverend Fox.

One witness, Private William B. Bednar, found himself floating in oil-smeared water surrounded by dead bodies and debris. "I could hear men crying, pleading, praying," Bednar recalls. "I could also hear the chaplains preaching courage. Their voices were the only thing that kept me going."

Another sailor, Petty Officer John J. Mahoney, tried to reenter his cabin but Rabbi Goode stopped him. Mahoney, concerned about the cold Arctic air, explained he had forgotten his gloves.

"Never mind," Goode responded. "I have two pairs." The rabbi then gave the petty officer his own gloves. In retrospect, Mahoney realized that Rabbi Goode was not conveniently carrying two pairs of gloves, and that the rabbi had decided not to leave the Dorchester.

By this time, most of the men were topside, and the chaplains opened a storage locker and began distributing life jackets. It was then that Engineer Grady Clark witnessed an astonishing sight. When there were no more lifejackets in the storage room, the chaplains removed theirs and gave them to four frightened young men. "It was the finest thing I have seen or hope to see this side of heaven," said John Ladd, a survivor who saw the chaplains' selfless act. Ladd's response is understandable. The altruistic action of the four chaplains constitutes one of the purest spiritual and ethical acts a person can make.

As the ship went down, survivors in nearby rafts could see the four chaplains—arms linked and braced against the slanting deck. Their voices could also be heard offering prayers.

Of the 902 men aboard the U.S.A.T. Dorchester, 672 died, leaving 230 survivors. When the news reached American shores, the nation was stunned by the magnitude of the tragedy and heroic conduct of the four chaplains.

"Valor is a gift," Carl Sandburg once said. "Those having it never know for sure whether they have it until the test comes." That night Reverend Fox, Rabbi Goode, Reverend Poling and Father Washington passed life's ultimate test. In doing so, they became an enduring example of extraordinary faith, courage and selflessness.

On December 19th, 1944, a ceremony was held at the post chapel at Fort Meyer, VA, attended by the chaplains’ next-of-kin. The Distinguished Service Cross and Purple Heart were awarded posthumously by Lt. Gen. Brehon B. Somervell, Commanding General of the Army Service Forces. And on January 18th, 1961, a one-time only posthumous Special Medal for Heroism, created by Congress to honor this singular event, was awarded by the President Eisenhower to the four chaplains for their sacrifice.

When giving up his life jacket, Rabbi Goode did not call out for a Jew; Father Washington did not call out for a Catholic; nor did the Reverends Fox and Poling call out for a Protestant. They simply gave their life jackets to the next man in line. And when the survivors recount the comforting prayers, prayers from four different faiths cutting through the black night in a haunting co-mingling of English, Hebrew, and Latin, I am quite sure that none of those men shivering in lifeboats or floating in the freeing water thought of censuring the Chaplains or demanding an apology because each Chaplain had linked arms with a man of a different faith, “on the same stage,” each praying to God as he understood him. . .

I am sure that all they felt was gratitude for the lifejackets and gloves, for the comfort and the kindness . . . and for the privilege of witnessing the awe inspiring sacrifice of the Four Chaplains. . . Four faiths, one heart, one God.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed