By Meg Langford

"TO AN ATHLETE DYING YOUNG"

(An excerpt from Liberty’s Tyranny: Falwell’s Folly)

I know my way around a classroom. I know that I know, because I understand that there are times when you have to stop being the Bohemian grad ass instructor, the cool Sutherland teacher from "Animal House", the teach’ who is everybody's pal—and you have to start being the bastard. The drill sergeant. The prick.

I was up to it: I gave low grades. I insisted on do-overs. I failed people. I turned them in for cheating. And they got convicted.

I remember one particularly thorny semester. I was done with all of my PhD course work. I had done well. I had quite nearly a 4.0. Annoying little overachiever that I have always been, I had taken more than enough credits to graduate. I love being in school. I could happily be "a lifer". I and my seemingly congenial committee had been through four drafts of my dissertation, “Resignations in Protest”, so it was all but rubber-stamped. The orals, as is often the case in the liberal arts, should have been something of a rubber stamp as well.*** Life was good.

***I know some may disagree with this. But at the time, at the University of Maryland, if you had hashed through years of your Masters (which I had gotten at The American University in Washington D.C.) and then a doctoral program, followed the protocols, and dutifully rewrote and revised whatever they told you, whenever they told you, it was usually a matter of course that you would finally be awarded your doctorate. The precious PhD.

I was teaching some intro courses for the speech department, to whittle the tally off of my giant tuition bill, and I will never forget the day that two gigantic black kids strode into my class. Man, these guys were huge. I figured they had to be part of the Maryland Terrapins, and it turned out I was right. No big deal. I loved teaching. Everybody and anybody. All kinds of students provided all kinds of challenges, and often it seemed to me that I learned more from them than they did from their teacher.

I remember one jock in particular, a football player named Aziz Abdur-Ra'oof, who came to me at the beginning of that same semester and told me that he knew being a professional athlete was a brutal career which could be all too short, and he wanted to get all he could out of this speech class, so that he could have life after football. Because Aziz was a great guy, and a dedicated student, he got both: a pro-ball career with the Kansas City Chiefs, then he won a prestigious appointment to the post of Director of Student Welfare and Career Development at the University of Maryland. I remember during that semester, he received some razzing about losing his shoe while on the field, during a game with Clemson. But seriously, this was a great kid. This is how it's done.

But back to the other two Terrapins.

*************

Sometimes, when I am blue and feeling powerless in the face of a big evil world, I like to think that I was personally responsible for toppling a Monolithic and Corrupt Empire called the Lefty Driesel Athletic Department.

What is so very cool about this fantasy is that a.) It is true.

b.) And if I happen to be a whit wrong, and it is not entirely true, then I know it to be mostly true.

It happened like this:

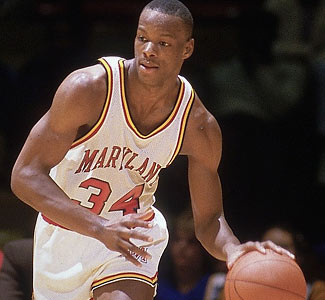

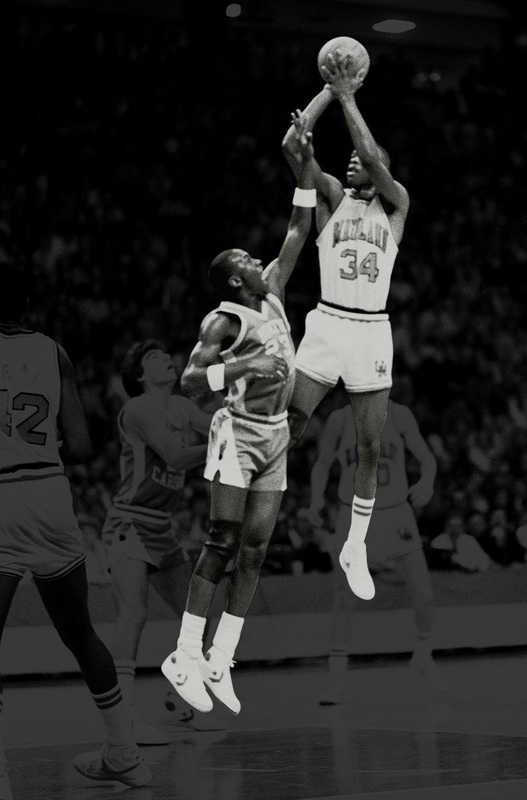

1.) These two tall, handsome ball players who strode into my class that first day of semester? These guys happened to be named Tony Massenburg and Len Bias.

2.) They never came to class. (Actually, that is not entirely true. In a class that met Monday-Wednesday-Friday, three times a week, meaning about 48 class meetings per semester; they each came to class about three times. Total.)

3.) When I received in my teacher's IN box a couple of evaluation forms, requesting a summary of how they were doing in the class, I wrote "F" in large red letters across both of their forms, explaining that they had never come to class except for that first day.

4.) They both immediately showed up for the next class, along with two bright kids, white sidekicks, who, as it turns out, were their tutors.

5.) Within days, both students—Bias and Massenburg—turned in papers that sounded like acceptance speeches by Pulitzer Prize Winners in Journalism.

6.) I grew suspicious.

6b.) Let's be real. There was no practical way to bust them on this. Oh, sure, I could have cornered both of them, and cross examined them about “their” papers—the ideas they put forth, the vocabulary they used, etcetera. (In fact, that same semester, there was a psych professor who sprang a pop quiz on his whole class, the entire purpose of which was to use the big words that each of his power athlete students had used in "their" papers. All the athletes got all the words wrong. Of course.) But me, I had a back-up plan. There were some in-class essay exams coming up in my class, and there was no way that they could fake those. And as for the group exercises—well, if the athletes didn't show up to participate in them, they didn't show. The "F's" would hold. It's not that I wanted to fail these kids. In fact I hated it. That meant, by implication, that I had failed them. It's just that the papers which were turned in, allegedly written by the athletes, were insultingly transparent. And never come to class? I mean, really.

Then, things got more interesting. Not that I needed this to sway my plan, but other students began to approach to me, wanting to talk privately, wanting to know if I was going to pass these kids with their tutor-written papers and their perpetual absences. I remember one kid distinctly. He had the bad skin and perennially greasy hair that only comes from working in a fast food restaurant twenty, thirty, forty hours a week. I know because I was that kid once. It seems that no matter how much you bathe, you can never get the grease from the fryer out of your hair or your pores. No matter how hard you scrub, you always reek of that distinctive stench that only wafts from one sordid source—the dumpster of a fast food restaurant. It smells like nothing else in the world.

I knew this kid was killing himself, working full time and going to school full time. And he had watched, over the semesters, as all the tall, beautiful athletes strode around campus, but rarely into class, driving scholarship sports cars, living large, being treated like celebrities, and never being held accountable. "You aren't going to pass those two guys just because they're on the team, are you?" he asked me. I will never forget that kid's eyes. It was the look of a kid who knew, just knew, that life was full of injustices, and that he was usually going to be on the wrong end of them.

7.) Mid-Semester came, and I turned in more "F"s, to reflect the continued absences from class of Len and Tony. Lefty had even stooped to sending their tutors to my class, in lieu of the students, to take notes, can you imagine the nerve?

8.) Then, it got creepy. Seriously. After class, I would be accosted by these creatures, following me down the halls, out to my car. I was never clear if they were athletes or tutors; what was made clear is that if these two basketball players had "F's" coming out of my class, it was jeopardizing the ability of these two athletes to continue playing. They had to maintain a certain GPA, they couldn’t be flunking a class, or they couldn’t play. I was threatening the whole team. I was going to cost Maryland the Championship. Clearly, I was the problem.

And all of this, by the way, meant Maryland losing the chubby bucks. I cannot, in all honesty, say that they threatened me with anything as awful as physical violence. They just kept saying how much it would mean to the school if I could just give the boys some passing grades, and how that would be good for everybody, good for all of us. Them and me. The conversation always went the same way. I said they needed to come to class. They asked couldn’t I give the boys a break? What kind of a break, I asked? I was willing to work around the game schedules, whatever they needed. But still, the two athletes were no shows.

9.) I start getting weird hang up calls at night.

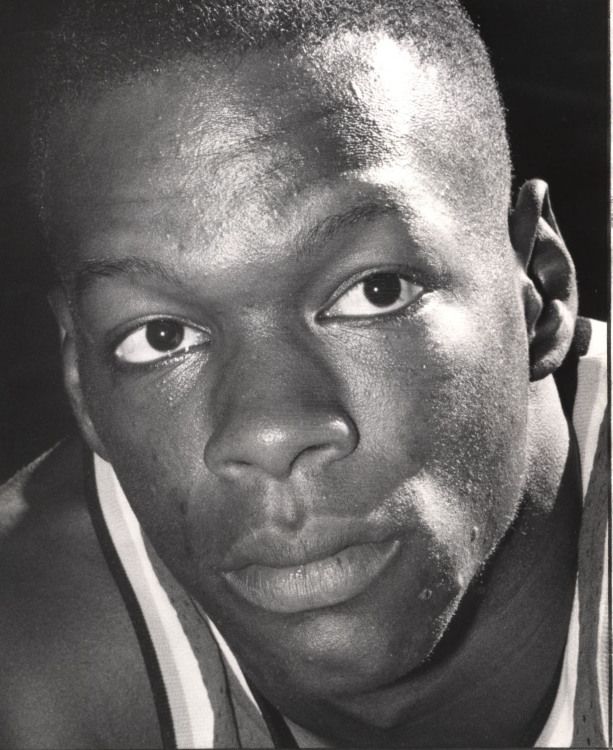

10.) It's decision time: I hold out and give Len a failing grade. I swear to God, this isn’t personal. How could it be, I never knew the kid. From the few times he came to class, he did seem like a hell of a nice and charismatic guy. But he just never came to even one tenth of the total classes that semester.

11.) Then, it happened. Tony Massenburg did a really boneheaded thing. Even more boneheaded than having a Pulitzer Prize level paper turned in on his behalf. Even more boneheaded than cheating on a multiple choice question. He copied verbatim the essay answer of the honor student sitting next to him. Cripes.

Of course, I had no choice. I turned him in. He was found guilty and narrowly avoided total expulsion, but he was benched from the team for a year. With Len graduating, Massenburg had been the team's great hope. I was a pariah, to say the least.

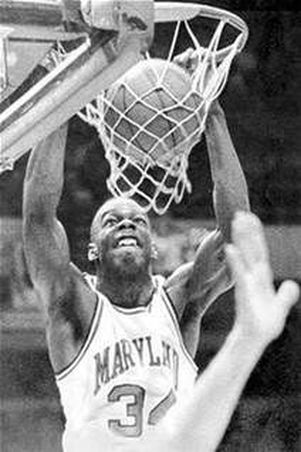

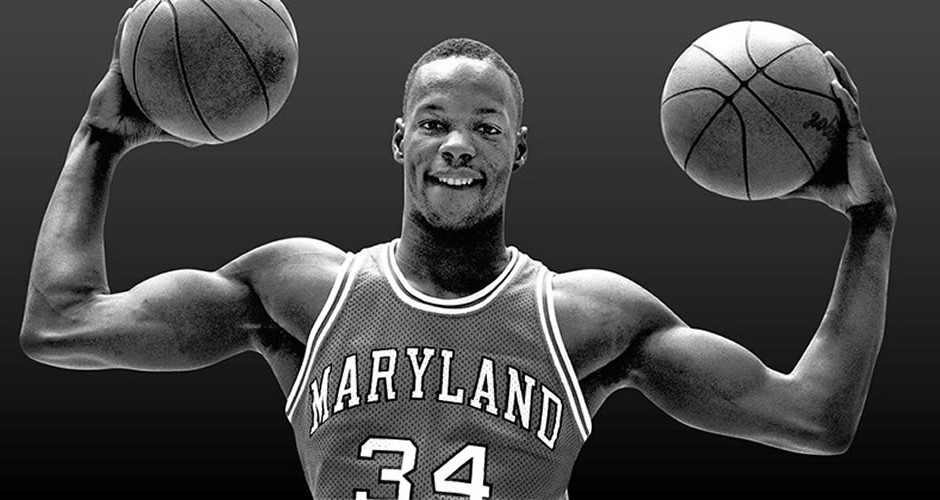

12.) THE TRAGEDY. Within a couple of weeks, Len Bias—considered by so many people to be the most talented and promising college hoops player of all time—was dead of a cocaine overdose. And this just hours after he was riding high on his triumphant signing with the Boston Celtics; he was nothing less than the second overall pick of the 1986 NBA draft. He was a god to his fans. He was wearing the Laurel on his head, and Reeboks on his feet, and from the way he could dunk, it would seem those Reeboks surely had wings. He had just signed a 1.6 million dollar contract with the famed shoe company, and he announced that his first plans with the money were to buy his mother her long overdue Mercedes. But, upon returning to D.C. from Boston, he partied a little too hard. Sic gloria transit mundi.

13.) Within a couple of days of that, I received a letter asking me to remove myself from the graduate program. They had determined that I had flunked out.

THE FALLOUT

But with all of these tragic endings (Lenny’s death tore us all up; he was so young and promising), there was also a beginning. The beginning of questions, of a search for answers, and of an excoriating investigation by the authorities.

Wendy Whittemore, the basketball team's academic counselor, resigned her post over "philosophical differences" with Lefty. Perhaps the kind of philosophical differences that Wendy had were decisions like the one Lefty made on the night of Len Bias's death: Lefty called Len Bias's roommate in the middle of the night, and told him to make sure that all drug paraphernalia was removed from the same room where Len Bias had overdosed just minutes earlier.

Lefty Driesel knew damn well that his players were on coke, and if that made them run faster, jump higher, and score into the stratosphere, then so be it. Swapping urine samples for drug tests was a joke, it was so easy, and no athletes were held accountable for anything, as long as they got the ball through the hoops, and continued to rake in the revenue. (Never has there been a coach more polar opposite to the Wizard of Westwood than Lefty Driesel.)

Lefty Driesel treated his black players, all his players, like—like plantation workers, before the war. You know the word I am thinking of, but it is not a word I use.

Here it is: all you have to do, if you're a jock, in order to have a half-way decent life after college, is get a C- average as a physical education major.

But it was common knowledge—and this is born out by statistics—that Lefty didn't give a good goddam if his boys graduated. Year after year, kids used up their eligibility without graduating. The practical reality and harsh translation is this: they had played the allowed four years of ball, but had no degree to show for it. Even though they could have lowered their sites to being phys ed majors, and gotten through with the help of a legitimate tutor, and still have gotten their degree scraping by with a "C-" average, Lefty cared so little for his players that to hell with them, he didn't even see to it that they accomplished something as minimal and manageable as that. What happened to their futures after they had finished winning for the Terrapins, Lefty just didn't care.

Len Bias, for example, was a full twenty one credits short of his graduation requirements at the time that he used up his eligibility.

That means that these poor exploited kids, superstars for a brief and shining moment, won't even be able to get a job teaching high school ball after college.

They can't even be Ken Tanaka.

*************

It was a sad and confusing time in my life. Not very much bad had happened to me up to that point. But let's not forget, it was a much sadder time for the parents of Len Bias.

Imagine being Len’s Bias’s dad. In a scene so wrought with emotion that it seems like something out of a movie, Lenny's father was beyond grief, pacing back and forth at the hospital, crying and calling out “Not my son, not my boy!”

And as if the entire story is not tragic enough, what many do not know is that Lenny's brother was shot just a few years later. A good son, without a troubled history, he was caught up in a jewelry store altercation. He had done nothing wrong. It wasn’t gang related, it wasn’t a robbery. The jealous husband of a clerk felt sure that Jay Bias was flirting with his wife, and was angry enough to ambush Jay in the parking lot and put a bullet in his brain.

James Bias, the father of Lenny and Jay, has reacted to all of this tragedy in the most pro-active and positive way I can imagine: he has dedicated himself to speaking out for stricter hand gun laws.

Imagine being Lenny’s mom. Amazingly, Lonise Bias has spent her life making the best out of an unfathomable nightmare, traveling the country, talking to schools and communities about staying off drugs, and about striving for excellence, as did Lenny on the ball court ... and about maintaining one's faith in God, no matter what. I called her on the phone, once, and she told me that she thought Lenny's life had come to mean as much in death as it would have if he had lived. Surely she is living testament to that; her strength and her courage stand as inspiration to anybody who hears her story. Who hears her speak.

I can never forget Lenny. Oddly enough, our birthdays are less than one day apart.

I remember the denouement to this story so very vividly: I was surrounded by the Len Bias tragedy for a few days after it happened. One afternoon, just to escape—I needed desperately to escape all this—and so I went alone to a matinee. The movie "Out of Africa" was playing. Imagine how stunned I was when it got to the end of the movie, and Meryl Streep, as only she can, reads this poem over the grave of her dear lost beloved:

To An Athlete Dying Young

The time you won your town the race

We chaired you through the market-place;

Man and boy stood cheering by,

And home we brought you shoulder-high.

Today, the road all runners come,

Shoulder-high we bring you home,

And set you at your threshold down,

Townsman of a stiller town.

I stumbled out to my car. I remember I just sat there for a long time, thinking.

Smart lad, to slip betimes away

From fields where glory does not stay,

And early though the laurel grows

It withers quicker than the rose.

Finally the emotions that had been building up that entire semester broke through. I had a good cry. Actually, it wasn’t that good. It was pretty bad. Raw.

Eyes the shady night has shut

Cannot see the record cut,

And silence sounds no worse than cheers

After earth has stopped the ears.

I knew then. Somehow, some way, we had all failed Lenny, just a little. I kept thinking about all of the things that somebody, some one of us, could have, should have taught him. The matinee had been a long one.

Now you will not swell the rout

Of lads that wore their honours out,

Runners whom renown outran

And the name died before the man.

The sun was setting. It was a beautiful sunset. But it was time to get home. I had a team of my own to coach.

So set, before its echoes fade,

The fleet foot on the sill of shade,

And hold to the low lintel up

The still-defended challenge-cup.

And round that early-laurelled head

Will flock to gaze the strengthless dead,

And find unwithered on its curls

The garland briefer than a girl’s.

I couldn't finish my Raisinettes, and I cried all the way home.

"TO AN ATHLETE DYING YOUNG"

(An excerpt from Liberty’s Tyranny: Falwell’s Folly)

I know my way around a classroom. I know that I know, because I understand that there are times when you have to stop being the Bohemian grad ass instructor, the cool Sutherland teacher from "Animal House", the teach’ who is everybody's pal—and you have to start being the bastard. The drill sergeant. The prick.

I was up to it: I gave low grades. I insisted on do-overs. I failed people. I turned them in for cheating. And they got convicted.

I remember one particularly thorny semester. I was done with all of my PhD course work. I had done well. I had quite nearly a 4.0. Annoying little overachiever that I have always been, I had taken more than enough credits to graduate. I love being in school. I could happily be "a lifer". I and my seemingly congenial committee had been through four drafts of my dissertation, “Resignations in Protest”, so it was all but rubber-stamped. The orals, as is often the case in the liberal arts, should have been something of a rubber stamp as well.*** Life was good.

***I know some may disagree with this. But at the time, at the University of Maryland, if you had hashed through years of your Masters (which I had gotten at The American University in Washington D.C.) and then a doctoral program, followed the protocols, and dutifully rewrote and revised whatever they told you, whenever they told you, it was usually a matter of course that you would finally be awarded your doctorate. The precious PhD.

I was teaching some intro courses for the speech department, to whittle the tally off of my giant tuition bill, and I will never forget the day that two gigantic black kids strode into my class. Man, these guys were huge. I figured they had to be part of the Maryland Terrapins, and it turned out I was right. No big deal. I loved teaching. Everybody and anybody. All kinds of students provided all kinds of challenges, and often it seemed to me that I learned more from them than they did from their teacher.

I remember one jock in particular, a football player named Aziz Abdur-Ra'oof, who came to me at the beginning of that same semester and told me that he knew being a professional athlete was a brutal career which could be all too short, and he wanted to get all he could out of this speech class, so that he could have life after football. Because Aziz was a great guy, and a dedicated student, he got both: a pro-ball career with the Kansas City Chiefs, then he won a prestigious appointment to the post of Director of Student Welfare and Career Development at the University of Maryland. I remember during that semester, he received some razzing about losing his shoe while on the field, during a game with Clemson. But seriously, this was a great kid. This is how it's done.

But back to the other two Terrapins.

*************

Sometimes, when I am blue and feeling powerless in the face of a big evil world, I like to think that I was personally responsible for toppling a Monolithic and Corrupt Empire called the Lefty Driesel Athletic Department.

What is so very cool about this fantasy is that a.) It is true.

b.) And if I happen to be a whit wrong, and it is not entirely true, then I know it to be mostly true.

It happened like this:

1.) These two tall, handsome ball players who strode into my class that first day of semester? These guys happened to be named Tony Massenburg and Len Bias.

2.) They never came to class. (Actually, that is not entirely true. In a class that met Monday-Wednesday-Friday, three times a week, meaning about 48 class meetings per semester; they each came to class about three times. Total.)

3.) When I received in my teacher's IN box a couple of evaluation forms, requesting a summary of how they were doing in the class, I wrote "F" in large red letters across both of their forms, explaining that they had never come to class except for that first day.

4.) They both immediately showed up for the next class, along with two bright kids, white sidekicks, who, as it turns out, were their tutors.

5.) Within days, both students—Bias and Massenburg—turned in papers that sounded like acceptance speeches by Pulitzer Prize Winners in Journalism.

6.) I grew suspicious.

6b.) Let's be real. There was no practical way to bust them on this. Oh, sure, I could have cornered both of them, and cross examined them about “their” papers—the ideas they put forth, the vocabulary they used, etcetera. (In fact, that same semester, there was a psych professor who sprang a pop quiz on his whole class, the entire purpose of which was to use the big words that each of his power athlete students had used in "their" papers. All the athletes got all the words wrong. Of course.) But me, I had a back-up plan. There were some in-class essay exams coming up in my class, and there was no way that they could fake those. And as for the group exercises—well, if the athletes didn't show up to participate in them, they didn't show. The "F's" would hold. It's not that I wanted to fail these kids. In fact I hated it. That meant, by implication, that I had failed them. It's just that the papers which were turned in, allegedly written by the athletes, were insultingly transparent. And never come to class? I mean, really.

Then, things got more interesting. Not that I needed this to sway my plan, but other students began to approach to me, wanting to talk privately, wanting to know if I was going to pass these kids with their tutor-written papers and their perpetual absences. I remember one kid distinctly. He had the bad skin and perennially greasy hair that only comes from working in a fast food restaurant twenty, thirty, forty hours a week. I know because I was that kid once. It seems that no matter how much you bathe, you can never get the grease from the fryer out of your hair or your pores. No matter how hard you scrub, you always reek of that distinctive stench that only wafts from one sordid source—the dumpster of a fast food restaurant. It smells like nothing else in the world.

I knew this kid was killing himself, working full time and going to school full time. And he had watched, over the semesters, as all the tall, beautiful athletes strode around campus, but rarely into class, driving scholarship sports cars, living large, being treated like celebrities, and never being held accountable. "You aren't going to pass those two guys just because they're on the team, are you?" he asked me. I will never forget that kid's eyes. It was the look of a kid who knew, just knew, that life was full of injustices, and that he was usually going to be on the wrong end of them.

7.) Mid-Semester came, and I turned in more "F"s, to reflect the continued absences from class of Len and Tony. Lefty had even stooped to sending their tutors to my class, in lieu of the students, to take notes, can you imagine the nerve?

8.) Then, it got creepy. Seriously. After class, I would be accosted by these creatures, following me down the halls, out to my car. I was never clear if they were athletes or tutors; what was made clear is that if these two basketball players had "F's" coming out of my class, it was jeopardizing the ability of these two athletes to continue playing. They had to maintain a certain GPA, they couldn’t be flunking a class, or they couldn’t play. I was threatening the whole team. I was going to cost Maryland the Championship. Clearly, I was the problem.

And all of this, by the way, meant Maryland losing the chubby bucks. I cannot, in all honesty, say that they threatened me with anything as awful as physical violence. They just kept saying how much it would mean to the school if I could just give the boys some passing grades, and how that would be good for everybody, good for all of us. Them and me. The conversation always went the same way. I said they needed to come to class. They asked couldn’t I give the boys a break? What kind of a break, I asked? I was willing to work around the game schedules, whatever they needed. But still, the two athletes were no shows.

9.) I start getting weird hang up calls at night.

10.) It's decision time: I hold out and give Len a failing grade. I swear to God, this isn’t personal. How could it be, I never knew the kid. From the few times he came to class, he did seem like a hell of a nice and charismatic guy. But he just never came to even one tenth of the total classes that semester.

11.) Then, it happened. Tony Massenburg did a really boneheaded thing. Even more boneheaded than having a Pulitzer Prize level paper turned in on his behalf. Even more boneheaded than cheating on a multiple choice question. He copied verbatim the essay answer of the honor student sitting next to him. Cripes.

Of course, I had no choice. I turned him in. He was found guilty and narrowly avoided total expulsion, but he was benched from the team for a year. With Len graduating, Massenburg had been the team's great hope. I was a pariah, to say the least.

12.) THE TRAGEDY. Within a couple of weeks, Len Bias—considered by so many people to be the most talented and promising college hoops player of all time—was dead of a cocaine overdose. And this just hours after he was riding high on his triumphant signing with the Boston Celtics; he was nothing less than the second overall pick of the 1986 NBA draft. He was a god to his fans. He was wearing the Laurel on his head, and Reeboks on his feet, and from the way he could dunk, it would seem those Reeboks surely had wings. He had just signed a 1.6 million dollar contract with the famed shoe company, and he announced that his first plans with the money were to buy his mother her long overdue Mercedes. But, upon returning to D.C. from Boston, he partied a little too hard. Sic gloria transit mundi.

13.) Within a couple of days of that, I received a letter asking me to remove myself from the graduate program. They had determined that I had flunked out.

THE FALLOUT

But with all of these tragic endings (Lenny’s death tore us all up; he was so young and promising), there was also a beginning. The beginning of questions, of a search for answers, and of an excoriating investigation by the authorities.

Wendy Whittemore, the basketball team's academic counselor, resigned her post over "philosophical differences" with Lefty. Perhaps the kind of philosophical differences that Wendy had were decisions like the one Lefty made on the night of Len Bias's death: Lefty called Len Bias's roommate in the middle of the night, and told him to make sure that all drug paraphernalia was removed from the same room where Len Bias had overdosed just minutes earlier.

Lefty Driesel knew damn well that his players were on coke, and if that made them run faster, jump higher, and score into the stratosphere, then so be it. Swapping urine samples for drug tests was a joke, it was so easy, and no athletes were held accountable for anything, as long as they got the ball through the hoops, and continued to rake in the revenue. (Never has there been a coach more polar opposite to the Wizard of Westwood than Lefty Driesel.)

Lefty Driesel treated his black players, all his players, like—like plantation workers, before the war. You know the word I am thinking of, but it is not a word I use.

Here it is: all you have to do, if you're a jock, in order to have a half-way decent life after college, is get a C- average as a physical education major.

But it was common knowledge—and this is born out by statistics—that Lefty didn't give a good goddam if his boys graduated. Year after year, kids used up their eligibility without graduating. The practical reality and harsh translation is this: they had played the allowed four years of ball, but had no degree to show for it. Even though they could have lowered their sites to being phys ed majors, and gotten through with the help of a legitimate tutor, and still have gotten their degree scraping by with a "C-" average, Lefty cared so little for his players that to hell with them, he didn't even see to it that they accomplished something as minimal and manageable as that. What happened to their futures after they had finished winning for the Terrapins, Lefty just didn't care.

Len Bias, for example, was a full twenty one credits short of his graduation requirements at the time that he used up his eligibility.

That means that these poor exploited kids, superstars for a brief and shining moment, won't even be able to get a job teaching high school ball after college.

They can't even be Ken Tanaka.

*************

It was a sad and confusing time in my life. Not very much bad had happened to me up to that point. But let's not forget, it was a much sadder time for the parents of Len Bias.

Imagine being Len’s Bias’s dad. In a scene so wrought with emotion that it seems like something out of a movie, Lenny's father was beyond grief, pacing back and forth at the hospital, crying and calling out “Not my son, not my boy!”

And as if the entire story is not tragic enough, what many do not know is that Lenny's brother was shot just a few years later. A good son, without a troubled history, he was caught up in a jewelry store altercation. He had done nothing wrong. It wasn’t gang related, it wasn’t a robbery. The jealous husband of a clerk felt sure that Jay Bias was flirting with his wife, and was angry enough to ambush Jay in the parking lot and put a bullet in his brain.

James Bias, the father of Lenny and Jay, has reacted to all of this tragedy in the most pro-active and positive way I can imagine: he has dedicated himself to speaking out for stricter hand gun laws.

Imagine being Lenny’s mom. Amazingly, Lonise Bias has spent her life making the best out of an unfathomable nightmare, traveling the country, talking to schools and communities about staying off drugs, and about striving for excellence, as did Lenny on the ball court ... and about maintaining one's faith in God, no matter what. I called her on the phone, once, and she told me that she thought Lenny's life had come to mean as much in death as it would have if he had lived. Surely she is living testament to that; her strength and her courage stand as inspiration to anybody who hears her story. Who hears her speak.

I can never forget Lenny. Oddly enough, our birthdays are less than one day apart.

I remember the denouement to this story so very vividly: I was surrounded by the Len Bias tragedy for a few days after it happened. One afternoon, just to escape—I needed desperately to escape all this—and so I went alone to a matinee. The movie "Out of Africa" was playing. Imagine how stunned I was when it got to the end of the movie, and Meryl Streep, as only she can, reads this poem over the grave of her dear lost beloved:

To An Athlete Dying Young

The time you won your town the race

We chaired you through the market-place;

Man and boy stood cheering by,

And home we brought you shoulder-high.

Today, the road all runners come,

Shoulder-high we bring you home,

And set you at your threshold down,

Townsman of a stiller town.

I stumbled out to my car. I remember I just sat there for a long time, thinking.

Smart lad, to slip betimes away

From fields where glory does not stay,

And early though the laurel grows

It withers quicker than the rose.

Finally the emotions that had been building up that entire semester broke through. I had a good cry. Actually, it wasn’t that good. It was pretty bad. Raw.

Eyes the shady night has shut

Cannot see the record cut,

And silence sounds no worse than cheers

After earth has stopped the ears.

I knew then. Somehow, some way, we had all failed Lenny, just a little. I kept thinking about all of the things that somebody, some one of us, could have, should have taught him. The matinee had been a long one.

Now you will not swell the rout

Of lads that wore their honours out,

Runners whom renown outran

And the name died before the man.

The sun was setting. It was a beautiful sunset. But it was time to get home. I had a team of my own to coach.

So set, before its echoes fade,

The fleet foot on the sill of shade,

And hold to the low lintel up

The still-defended challenge-cup.

And round that early-laurelled head

Will flock to gaze the strengthless dead,

And find unwithered on its curls

The garland briefer than a girl’s.

I couldn't finish my Raisinettes, and I cried all the way home.